bioGraphic: A Grand Experiment on The Grasslands

After years of decline and arguable neglect, the lesser prairie-chicken (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus) was poised for a comeback in April 2014. The bird had finally scored a threatened listing under the Endangered Species Act—a big win for environmental groups after a long battle fought with petitions and lawsuits that highlighted the species’ plummeting numbers and increasing threats to its habitat. But it didn’t take long for industry to start fighting back.

In a lawsuit of its own, a group called the Permian Basin Petroleum Association argued that the listing was irrational and unfair. Oil and gas companies had already committed tens of millions of dollars to efforts designed to protect or improve lesser prairie-chicken habitat, says Ben Shepperd, president of the Association. A listing now would cost the industry billions of dollars in lost revenue. The organization had one goal: Get the bird off the list.

“There's literally hundreds of thousands of jobs at stake here in this five-state region—untold billions of dollars in tax revenue, benefits to local communities and schools and hospitals,” Shepperd says. “When the bird was first listed, we were very concerned as an industry that it was going to have a devastating effect, a very chilling effect on oil and gas development.”

Environmental groups saw just as much at stake on the other side. The lesser prairie-chicken lives only in the grasslands of the central U.S., making it an icon of America’s unique natural heritage and a beacon of an imperiled ecosystem. With its bushy orange eyebrows, flashy mating displays, and position in the political spotlight, the bird also represents many other, less-prominent species, such as dunes sagebrush lizards, prairie dogs, swift foxes, lark buntings, and grasshopper sparrows, that share the same habitat.

“We sort of viewed the chicken as a bang-for-the-buck effort,” says Jay Tutchton, a recently retired environmental lawyer who represented the Center for Biological Diversity and was involved in the legal effort to list the species. “If you took care of the chicken, you’d probably be taking care of the lizard, and the swift fox, and the prairie dogs, and the ferruginous hawks, and all sorts of other things that currently aren’t as close to the edge as the chicken, but are headed that way.”

Up to 99 percent of American grasslands have been degraded or destroyed, adds Clay Nichols, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist in Arlington, Texas, who grew up on the edge of prairie-chicken country in New Mexico and started surveying for the birds when he was an undergraduate at Eastern New Mexico University in the late 2000s. “The lesser prairie-chicken is an indicator species of these national treasures of the continental United States,” he says of the country’s native grasslands. “If the lesser prairie-chicken is struggling, it’s for a reason: The grasslands of the Great Plains are struggling.”

Beyond practical arguments about threats to jobs and habitats and food webs, the lesser prairie-chicken has also long attracted deep affection. The bird’s courtship dance during mating season is dramatic enough to draw tourists. “What environmentalists have tried to do is save these species so that future generations can also enjoy them and that they’re not looking at lesser prairie-chickens in a box in a museum,” Tutchton says. “It would be tragic if we lose the chicken. The prairies will be a bit lonelier without this interesting and unique bird.”

Sue Selman is attuned to this potential kind of loneliness. A native of northern Oklahoma, Selman runs a guest ranch that doubles as a featured location in an annual lesser prairie-chicken festival each April. The ranch’s website, which is full of lesser prairie-chicken photographs, urges visitors to start their day with a hot, home-cooked breakfast and then “jump in the truck and head out for an early morning view of the Lesser Prairie Chicken.”

A few dozen of the birds used to breed on and near her land, Selman says, but she hasn’t seen them in a few years, and she has started to worry. “I think they’re gone—it just breaks my heart,” says Selman, who leads birding tours for festival-goers and other visitors. “I like the experience of people coming out here and enjoying the prairie-chickens and the prairie. The thought of not having those birds makes me really sad.”

It took about a year for the Permian Basin Petroleum Association’s lawsuit to reach a West Texas courtroom on a steamy June day in 2015. After months of legal wrangling, the foreseeable fate of the lesser prairie-chicken came down to this: a half-empty courtroom, a judge who asked a lot of questions without expressing a hint of emotion, and three months of waiting for a ruling. Finally, the decision came in: The judge had sided with the oil and gas industry, ruling to de-list the lesser prairie-chicken.

The decision surprised parties on both sides. And it marked yet another pivotal moment in a battle over a bird that had been going on for decades. Deep in the heart of oil and gas country, the plight of the lesser prairie-chicken has, in that time, come to offer a unique window into the inner workings of the Endangered Species Act—its potential and its limitations. Because the bird lives primarily on private land, it also raises questions about how a federal law can—or should—be implemented to protect it.

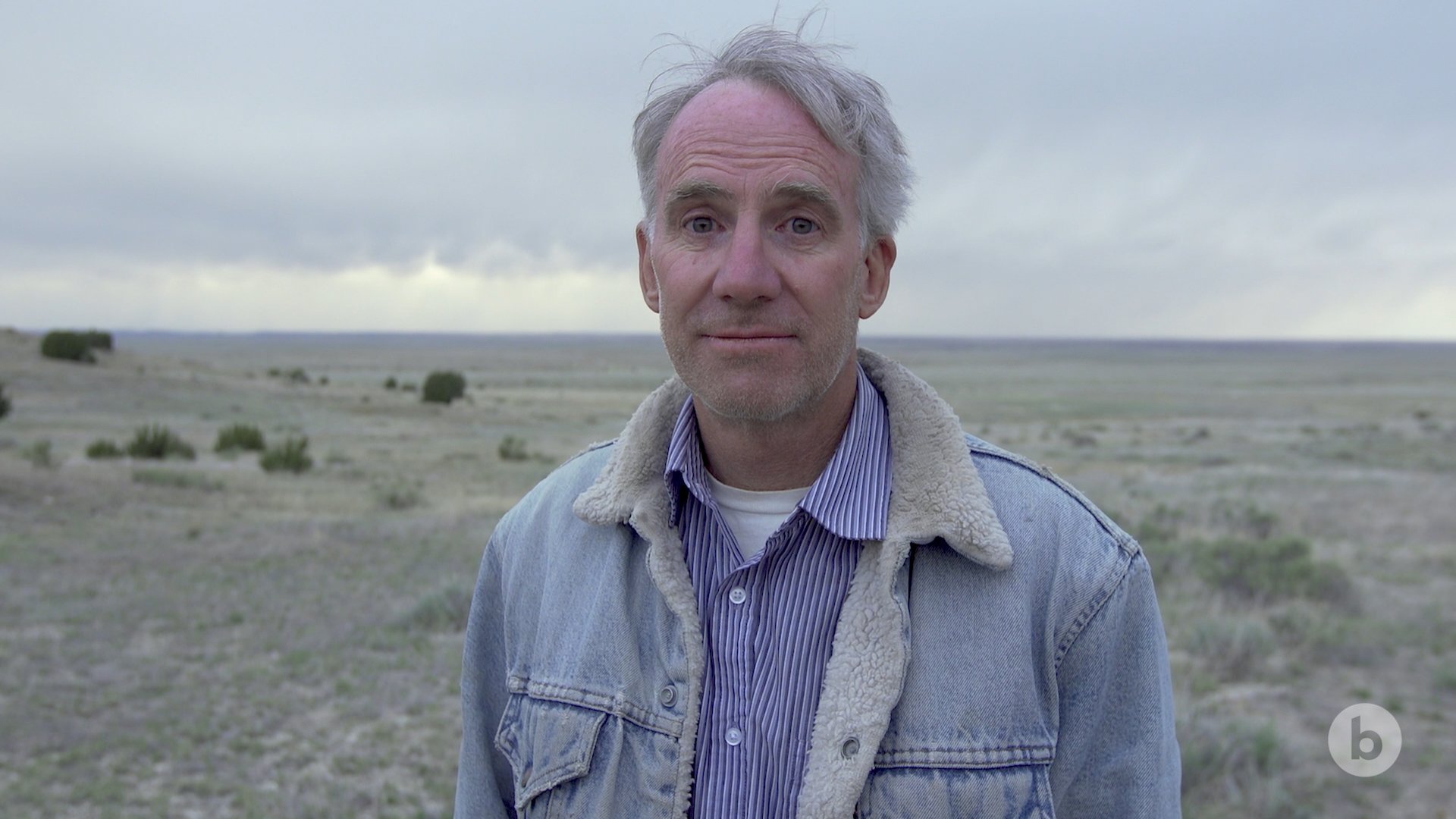

“There’s no doubt that the species needs some help,” says Christian Hagen, an ecologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis, who studies lesser prairie-chicken conservation efforts in the southern Great Plains. “The question before all of us is: What are the best methods to help?”

As yet another petition works its way through the federal review process, some experts think the lesser prairie-chicken may herald the rise of a new model of conservation—one that relies less on the hammer of the law and more on the power of negotiation. If the strategy works—even amidst shifting political winds—it could alter the future for other species, too, by acknowledging the complex and competing interests on lands where development and conservation increasingly struggle to coexist.

---

See the rest of the story here.